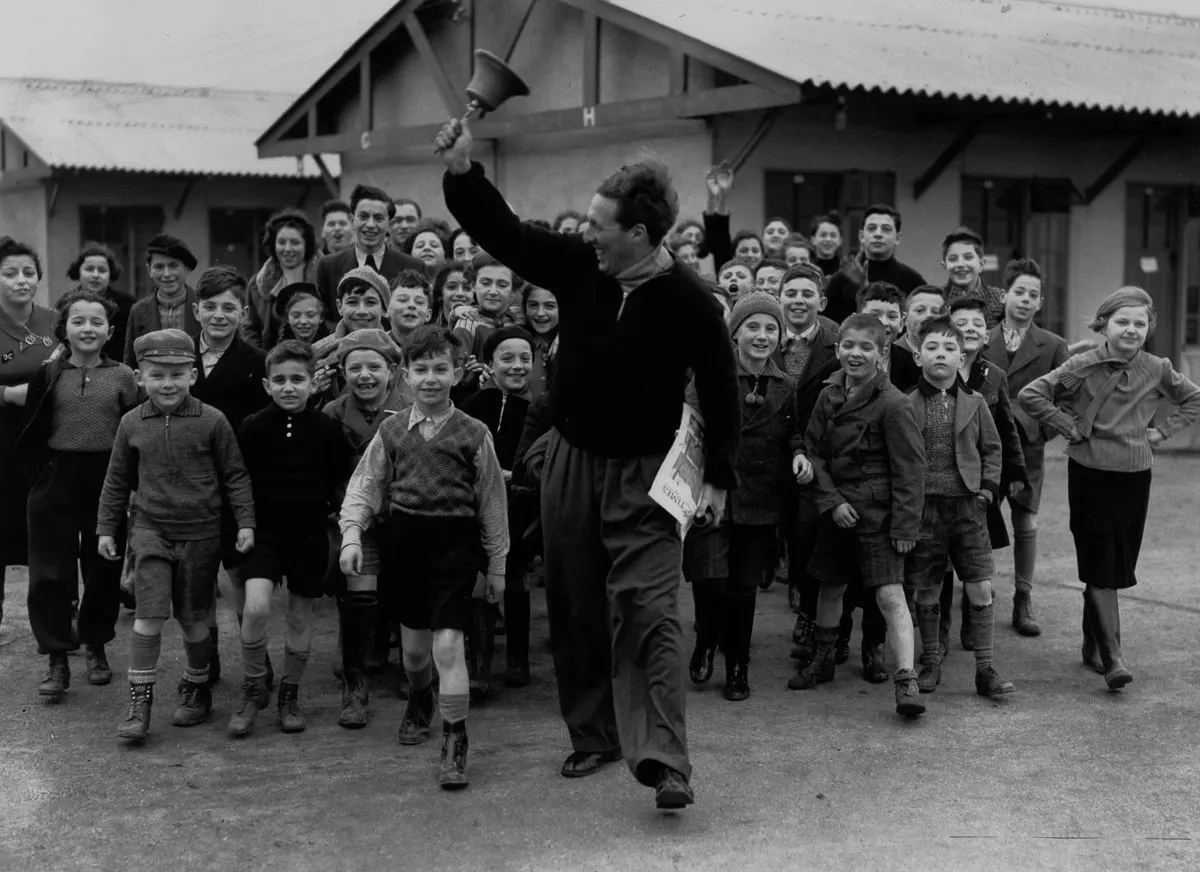

A camp leader rings the dinner bell for refugees at the Dovercourt holiday camp, 1939. (Photo by Reg Speller).

Imagine getting on a train and leaving your parents and your family behind. Imagine arriving in a new place, where you don’t speak the language and where everything is different.

People wear clothes that seem strange; the food is different too. Imagine feeling that great danger looms and threatens those you love most, yet you have no idea what might be happening to your family back home.

This is what happened to ten thousand children who escaped Nazi-occupied countries on the Kindertransport, a rescue effort that took place from 1938 to 1939.

Kindertransport, (German for “Children Transport”) was the nine-month rescue effort authorized by the British government and conducted by individuals in various countries and by assorted religious and secular groups that saved some 10,000 children, under age 17 and most of them Jewish, from Nazi Germany, Austria, Czechoslovakia, Poland and the free city of Danzig (Gdańsk) by relocating them to the United Kingdom.

The program began after the Kristallnacht pogroms of November 9–10, 1938, when Nazis attacked Jewish persons and property and conducted mass arrests, and largely ended on September 1, 1939, with the outbreak of World War II, although children continued to be rescued as late as 1940. The name Kindertransport came into use in the late 20th century.

Some of the first unaccompanied child refugees to arrive in England as part of the Kindertransport. December 2, 1938. (Photo by Fred Morley).

Within months of Adolf Hitler’s rise to power in Germany in 1933, tens of thousands of Jews left the country. However, that emigration quickly began to slow as it became increasingly difficult to obtain a visa.

U.S. Pres. Franklin Roosevelt responded to this “refugee problem”—that is, the inability of Jews stranded in Nazi Germany to find countries willing to offer them refuge—by proposing that a conference be held.

Beginning July 6, 1938, representatives from 32 countries met for 10 days in the French resort town of Évian-les-Bains.

Despite grand proclamations, little came of the Évian Conference. There were discussions of potential settlement locations, but most countries remained unwilling to admit new immigrants.

Jewish refugee children on their arrival in London on the Warszawa.

Following Kristallnacht, the British Parliament responded to calls for action by the British Jewish Refugee Committee with a debate in the House of Commons on November 21, 1938.

Although the British government had just imposed a new cap on Jewish immigration to Palestine as part of its mandate there, several factors contributed to the decision to permit an unspecified number of children under age 17 to enter the United Kingdom: the diligence of refugee advocacy, the growing awareness of anti-Jewish atrocities in Germany and Austria, and pro-Jewish sympathies among some high-placed Britons.

To “assure their ultimate resettlement” a £50 bond had to be posted for each of these children, who, it was assumed, would reconnect with their parents once the crisis had passed. They were admitted with temporary travel documents.

On December 1, 1938, less than one month after Kristallnacht, the first transport left Germany. It arrived at Harwich, England, the following day, bringing 196 children from a Jewish orphanage in Berlin that had been burned by the Nazis on November 9.

German-Jewish girl Helga Samuel is met by a Kindertransport agent upon arriving in Harwich. December 2, 1938. (Photo by Fred Morley).

The children went through extreme trauma during their extensive Kindertransport experience. This is often presented in very personal terms.

The exact details of this trauma, and how it was felt by the child, depended on the child’s age at separation, and on the details of his or her total experience until the end of the war, and even after that.

The primary trauma was the actual parting from the parents, bearing in mind the child’s age. How this parting was explained was very important: for example, “you are going on an exciting adventure”, or “you are going on a short trip and we will see you soon”.

Younger children, perhaps six and younger, would generally not accept such an explanation and would demand to stay with their parents.

There are many records of tears and screaming at the various railway stations where the actual parting took place. Even for older children, “more willing to accept the parents’ explanation”, at some point that child realised that he or she would be separated from his or her parents for a long and indefinite time.

The younger children had no developed sense of time, and for them, the trauma of separation was total from the very beginning.

A refugee is met by a Kindertransport agent. 1938.

Having to learn a new language, in a country where the child’s native German or Czech was not understood, was another cause of stress.

To have to learn to live with strangers, who only spoke English, and accept them as “pseudo-parents”, was a trauma. At school, the English children would often view the Kinder as “enemy Germans” instead of as “Jewish refugees”.

At the end of the war, there were great difficulties in Britain as children from the Kindertransport tried to reunite with their families.

Agencies were flooded with requests from children seeking to find their parents or any surviving member of their family.

Some of the children were able to reunite with their families, often traveling to far-off countries in order to do so. Others discovered that their parents had not survived the war.

In her novel about the Kindertransport titled The Children of Willesden Lane, Mona Golabek describes how often the children who had no families left were forced to leave the homes that they had gained during the war in boarding houses in order to make room for younger children flooding the country.

Among the children saved by the Kindertransport were future Nobel laureates Arno Penzias and Walter Kohn, and many others who, despite losing everything, would grow up to become prominent scientists, politicians, and artists.

Travel documents for children rescued in the Kindertransport. 1939.

Young refugees of the first Kindertransport after their arrival at Harwich, Essex, in the early morning of 2 December 1938.

A young refugee arrives at the Dovercourt holiday camp. 1938. (Photo by Fred Morley).

Young refugee Max Unger arrives at the Dovercourt holiday camp. (Photo by Fred Morley).

Josepha Salmon, 8, arrives at Harwich on her way to the Dovercourt holiday camp. (Photo by Fred Morley).

A German refugee studies English at the Dovercourt holiday camp. December 17, 1938. (Photo by Kurt Hutton).

A refugee takes a much-deserved rest after arriving at the Dovercourt holiday camp. December 17, 1938. (Photo by Kurt Hutton).

A German Jewish girl, newly arrived at the Dovercourt holiday camp. 1938. (Photo by Gerti Deutsch).

Refugees at their accommodations in England. 1938.

Refugees are served lunch at the Dovercourt Bay Holiday Camp near Harwich in Essex. (Photo by Kurt Hutton).

Two Etonian schoolboys give singing lessons to a group of Jewish refugees at Dovercourt holiday camp. 1939. (Photo by Reg Speller).

A refugee plays soccer at the Dovercourt holiday camp. (Photo by Kurt Hutton).

Miss W. Herford leads refugee children on a walk at the Dovercourt holiday camp. 1939. (Photo by Reg Speller).

German-Jewish teeangers serve lunch at the Dovercourt holiday camp. (Photo by Gerti Deutsch).

A refugee rings the dinner bell at the Dovercourt holiday camp. 1938. (Photo by Gerti Deutsch).

Jewish refugees eat lunch at the Dovercourt holiday camp. (Photo by Gerti Deutsch).

A refugee at the Dovercourt holiday camp.

A refugee at Dovercourt. (Photo by Kurt Hutton).

Refugees rest after arriving safely at Dovercourt holiday camp. 1938. (Photo by Gerti Deutsch).

Four of a group of 250 refugees arrive at Southampton on the U.S. ocean liner “Manhattan.” Of the 250 refugees, 88 were unaccompanied children. 1939.

11-year-old Otto Busch of Vienna with Mr. and Mrs. Guest, his host family in England. (Photo by Kurt Hutton).

Refugees play on the grounds of Dane Court Farm, which Sir Edmund Davies has turned into a school and refuge. 1939. (Photo by Fred Morley).

Jewish refugees at Harris House in Southport, Lancashire. The house was forced to close in 1940 as the British authorities believed that refugees over the age of 16 could be a security risk.

Refugees arrive in England aboard the American ocean liner “Manhattan.” 1939.

Flor Kent’s memorial at Liverpool Street station, relocated to the station’s concourse in 2011.