The crinoline appeared on the fashion scene in the mid-1800s and took its name from the French word crin (“horsehair”), a stiff material made using horsehair — and “linen.”

A crinoline (hoop) is defined as a framework consisting of round/oval circles (shaped like a hoop) of whalebone, wire, or cane used to extend the skirt.

The steel-hooped cage crinoline, first patented in April 1856 by R.C. Milliet in Paris, and by their agent in Britain a few months later, became extremely popular.

Steel cage crinolines were mass-produced in huge quantities, with factories across the Western world producing tens of thousands in a year.

Alternative materials, such as whalebone, cane, gutta-percha, and even inflatable caoutchouc (natural rubber) were all used for hoops, although steel was the most popular.

At its widest point, the crinoline could reach a circumference of up to six yards, although by the late 1860s, crinolines were beginning to reduce in size.

The size of the crinoline often caused difficulties in passing through doors, boarding carriages and generally moving about.

Crinolines were worn by women of every social standing and class across the Western world, from royalty to factory workers. This led to widespread media scrutiny and criticism, particularly in satirical magazines such as Punch.

In 1855, an observer of Queen Victoria’s state visit to Paris complained that despite the number of foreigners present, Western fashions such as the crinoline had diluted national dress to such an extent that everyone, whether Turkish, Scottish, Spanish, or Tyrolean, dressed alike.

Victoria herself is popularly said to have detested the fashion, inspiring a song in Punch that started: “Long live our gracious Queen/Who won’t wear crinoline!”

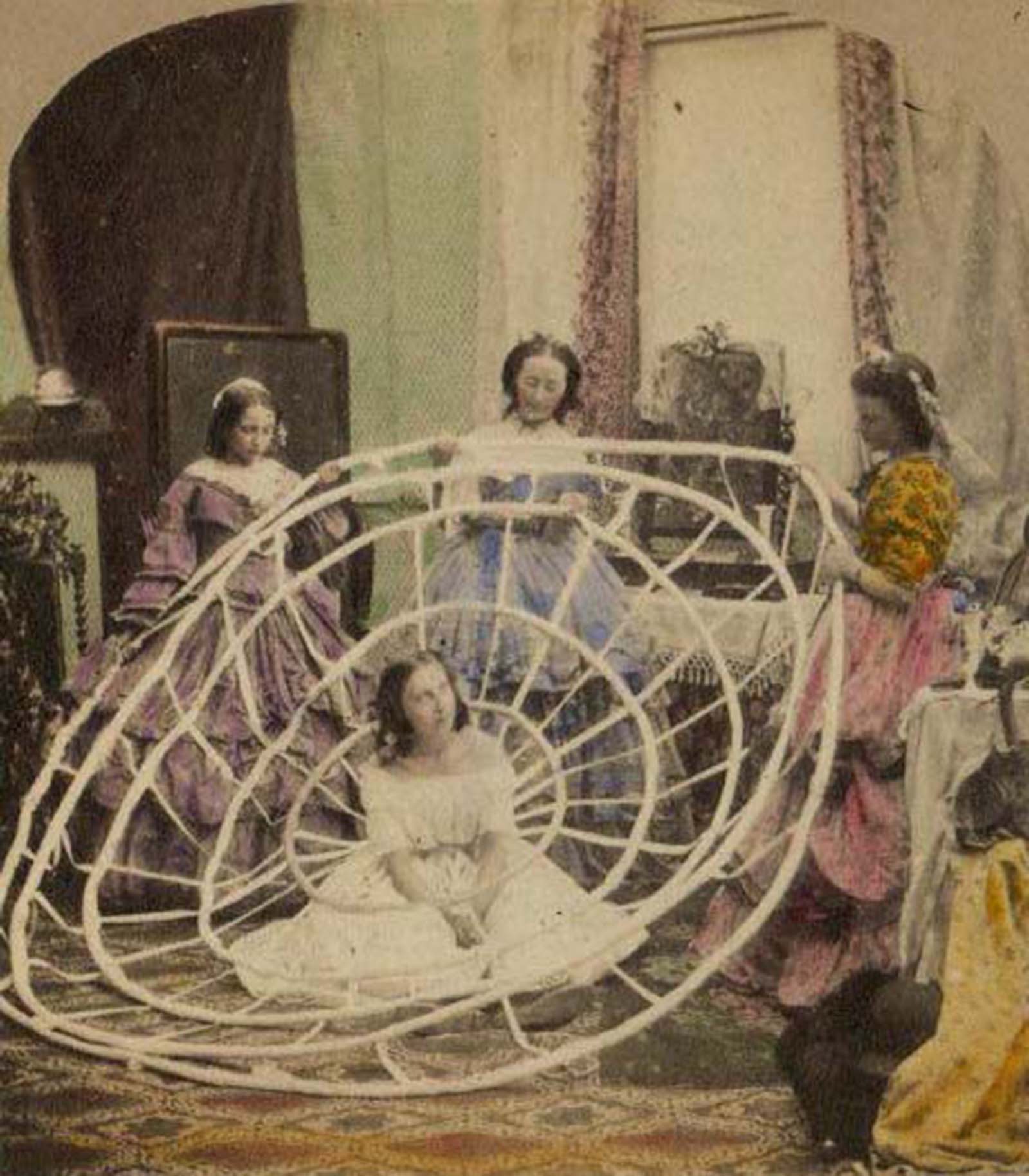

Coloured stereocard entitled ‘Putting on Crinoline’ depicting a woman being dressed in a crinoline, published by the London Stereoscopic Company, London.

Crinolines were also hazardous if worn without due care. Thousands of women died in the mid-19th century as a result of their hooped skirts catching fire. Alongside fire, other hazards included the hoops being caught in machinery, carriage wheels, gusts of wind, or other obstacles.

It is estimated that, during the late 1850s and late 1860s in England, about 3,000 women were killed in crinoline-related fires.

Although trustworthy statistics on crinoline-related fatalities are rare, Florence Nightingale estimated that at least 630 women died from their clothes catching fire in 1863-64.

One such incident, the death of a 14-year-old kitchenmaid called Margaret Davey was reported in The Times on 13 February 1863. Her dress, “distended by a crinoline,” ignited as she stood on the fender of the fireplace to reach some spoons on the mantelpiece, and she died as a result of extensive burns.

By the early 1870s, the crinoline fashion trend faded away and was replaced by the bustle. It has been periodically revived, most notably after World War II as part of Christian Dior’s New Look. Today, the crinoline is still worn on very formal occasions such as weddings.

These stereocards and images collected in this article are on display in the National Museum of Scotland in Edinburgh and offer a glimpse of the long-gone fashion trend of crinolines.

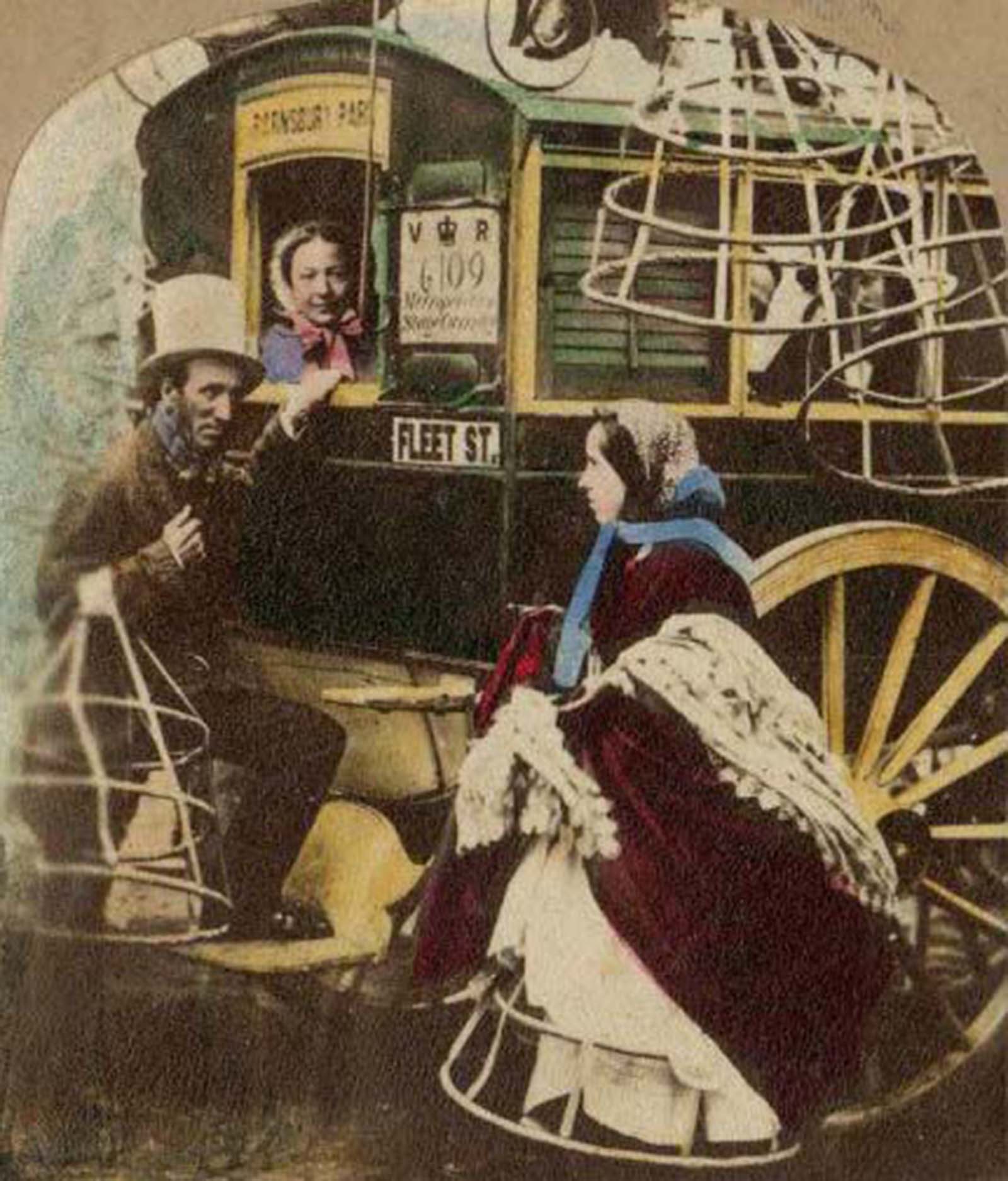

Colored stereocard entitled ‘New Omnibus Regulation’ depicting a woman in a crinoline trying to board an omnibus, by an unknown photographer, possibly 1861.

Colored stereocard entitled ‘The Rival Omnibuses’ by an unknown photographer.

Stereocard, part of The Howarth-Loomes Collection.

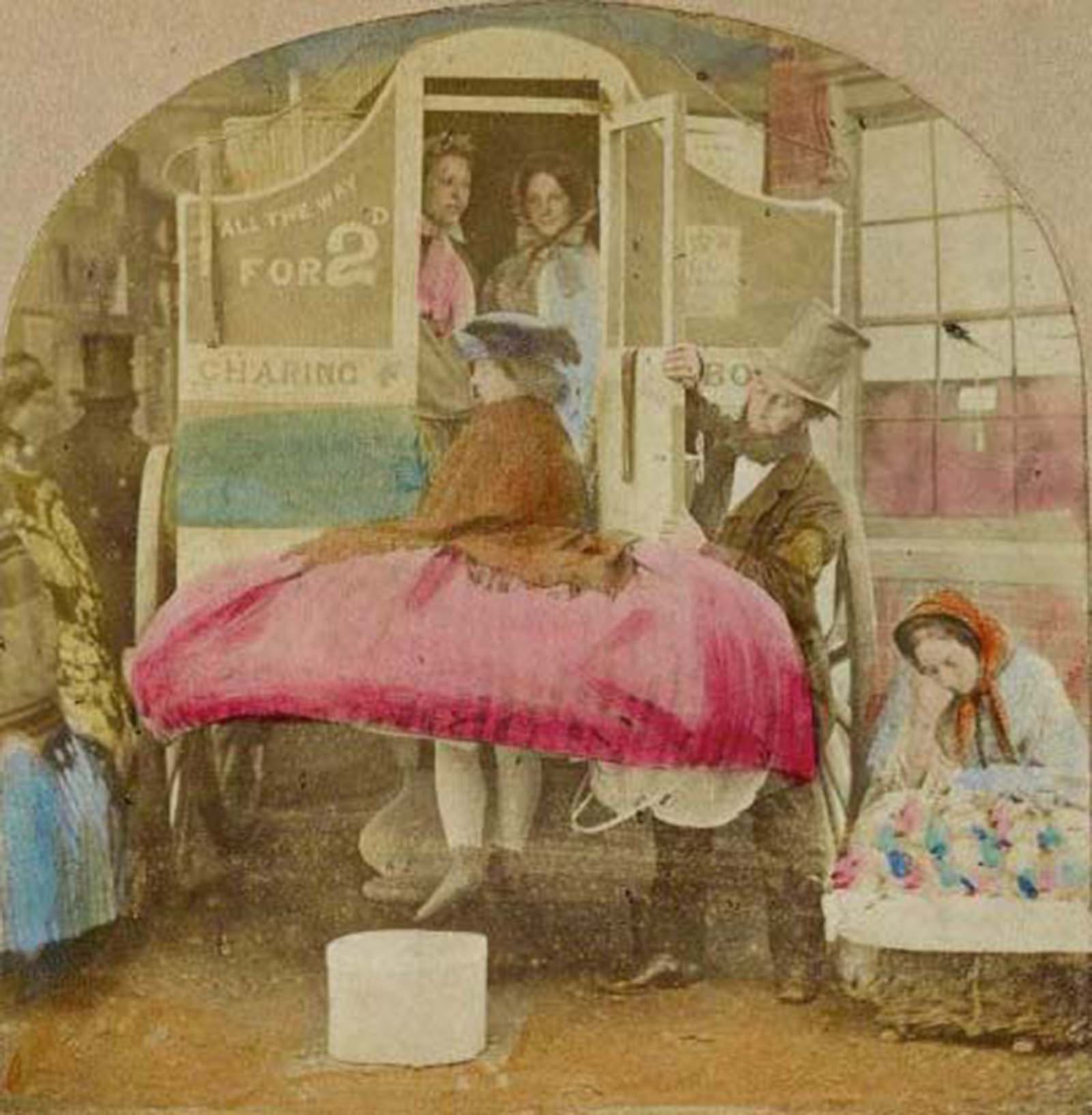

Stereocard entitled ‘Now ma-rm, say when’ depicting two men helping a lady on to a bus, by an unknown photographer.

Colored stereocard entitled ‘Putting on Crinoline’ depicting a woman being dressed in a crinoline, by an unknown photographer.

Stereocard depicting a man discovered under a ladies crinoline, by an unknown photographer.

Cage crinoline with steel hoops, 1865.

Sara Forbes Bonetta by Camille Silvy, 1862.

-1709301414.jpg)